The California Legislature passed the Budget Act of 2018, Senate Bill 840 (SB 840) and related budget bill Assembly Bill 1808 (AB 1808), on June 15 and 19, 2018.1 The Governor signed the budget bill for the 2018-19 fiscal year (the “Budget”) and AB 1808 on June 27, 2018. The following analysis addresses key child care and early education items in the Budget in light of recent funding history, as well as the availability of state and federal funding for child care in this year’s budget cycle.

Total funding for all California child care and development programs for fiscal year 2018-2019, including one-time funding, state preschool and afterschool program funding, increased by $628 million, to a total of $4.6 billion.2 This represents an overall 16% increase from the 2017-18 budget.3 Even after this year’s increase, annual spending for child care and preschool has not yet caught up to pre-recession levels when adjusted for inflation.4

The combination of one-time money (both Proposition 98 and non-98), state and federal funds, brings California’s total new investment in Early Care and Education (ECE) programs to over $900 million. Some of these dollars will become available in subsequent years.

California legislators have rightfully focused their attention and fiscal resources in this Budget on expanding the opportunities for our youngest and most vulnerable children, particularly children with disabilities and children under three years old.

While legislators have moved the early childhood infrastructure in a positive direction with this year’s budget, the actual number of vouchers to help families afford quality child care will increase by only 13,407, with most of those time-limited. That brings the number of children served through vouchers to 47,526.

In addition, 2,595 new full-day preschool spaces were added, bringing the total number of preschool children served to 168,478.

I. Overview of Child Care and Early Education Funding in FY 2018-2019

Funding for child care and development programs increased $628 million over the budget for the prior fiscal year, bringing the total to $4.6 billion. This total budget is funded with non- Proposition 98 general funds of $1.4 billion; $1.6 billion in Proposition 98; and $1.6 million in federal funds.

II. Analysis of Child Care Provisions in the California State Budget for Fiscal Year 2018-2019

The significant increases contained in this year’s budget package are highlighted below:

- $220.4 million to fund 13,407 new Alternative Payment Program voucher spaces. 11,307 CCDBG-funded vouchers start on July 1, 2018, using $204.6 million in CCDBG funds over a two year period. The vouchers will expire July 1, 2020, unless the increased federal funding continues. 2,100 General Fund slots begin September 1, 2018, and are ongoing. ($15.833 million General Fund (non-Proposition 98); $204.6 million CCDBG).

- $167 million one-time funds for the Inclusive Early Education Expansion Program. This will fund one-time competitive grants for infrastructure to high need school districts to create inclusive ECE classrooms. (Proposition 98).

- $114 million to fund increased caseload and higher reimbursement rates for all three stages of CalWORKs child care. (General Fund; federal TANF and CCDBG).

- $54 million to fund a 2.71% Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) for all non- CalWORKs child care programs and the state preschool program. ($30 million Proposition 98; $24 million General Fund).

- $48 million to increase the Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR) by 2.8%. Combined with the COLA above, the SRR increase for this year is 5.6%. ($32 million Proposition 98; $16 million General Fund).

- $39.7 million to increase the Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR) adjustment factors for infants, toddlers, children with exceptional needs, and children with severe disabilities. (General Fund).

- $38 million to annualize the Regional Market Rate (RMR) increase from last year’s adoption of the 2016 RMR Survey, and to make the hold harmless provisions permanent. This includes $24 million to annualize the cost of adopting the 75th percentile of the updated 2016 Regional Market Rate Survey as of January 1, 2018.5 It also includes $14 million to make the hold harmless provisions permanent. ($33 million General Fund; $5 federal funds).

- $21 million to annualize the Emergency Child Care Bridge Program cost. This funds short-term child care vouchers in participating counties for children in out-of-home placements, and navigators based in the local resource and referral agencies. ($11 million General Funds; $10 million Title IV-E).6

- $18 million to add 2,959 full-day slots in the state preschool program, and annualize costs of slots added April 1, 2018. These slots were part of the multi-year plan in the 2016- 17 budget agreement. (Proposition 98).

Analysis of the Enacted Budget

The Budget completes implementation of the final year of the multi-year budget agreed enacted for FY 2016-2017 which provided incremental, steady increases across the child care reimbursement rate structure to reflect increases in the state minimum wage and other market forces. It has also added over 13,000 preschool spaces. This year’s Budget also allows an additional 13,407 children to be served in the voucher program. The allocation of several hundred million to be used as one-time funds reflects the large current budget surplus, along with a reluctance to rely upon its continuation.

A. Modest Increase in Alternative Payment (AP) Vouchers; most are time-limited

Good, affordable child care creates stability and opens opportunities for children, families, and communities. The Legislature’s investments over the last four years have tilted heavily toward pre- school children (ages 3-5), much of that paid for with Proposition 98 dollars. Child care for infants and toddlers (ages 0-3) is still in the shortest supply, and is the most expensive to provide.

Before this budget year, California provided child care vouchers to just 32,000 children statewide. The Legislature added 2,100 ongoing vouchers and 11,307 time-limited vouchers, for a total increase of 13,407 vouchers.

The Budget funds the 11,307 time-limited vouchers with $204.6 million ($409 million over two years) of the increased CCDBG funds California is receiving to improve child care access.7 If, as expected, California continues to receive this increased CCDBG allocation in 2019-20, then these vouchers will continue for another two years, through FY 2021-2022. The Budget also provides an additional $16 Million in General Funds for 2,100 new AP vouchers, starting September 1, 2018. The annualized ongoing General Fund cost is $19 million.

Advocates and the Legislative Women’s Caucus had called for at least matching both the Senate and Assembly Legislative proposals which would have funded an additional 28,000 vouchers.

The Child Care Law Center looks forward to working with the Legislature and the new Governor next year to build on this year’s progress and continue to address this severe shortage of AP vouchers.

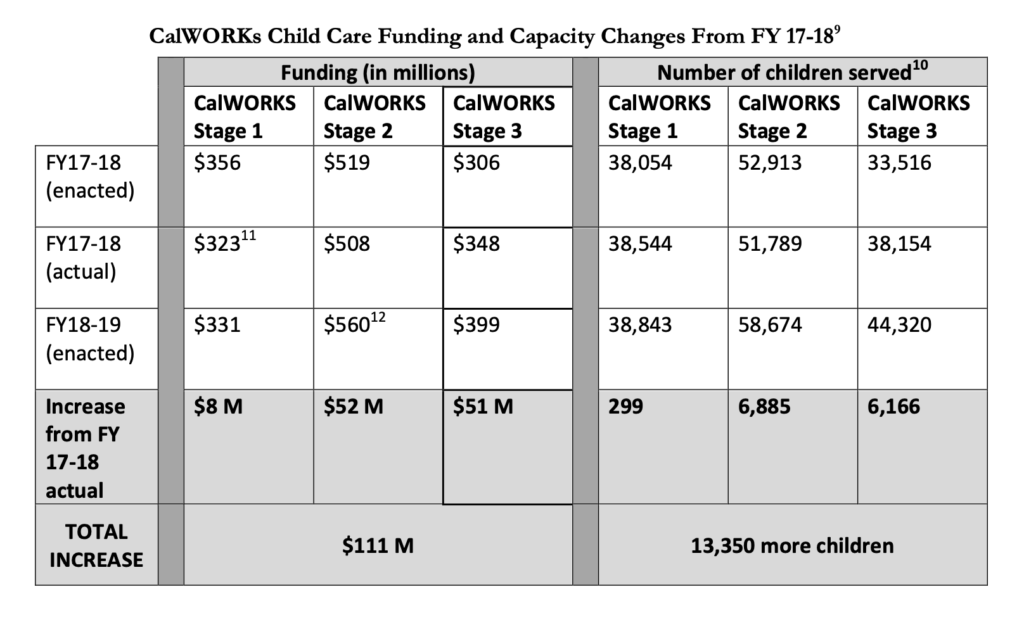

B. More Children in Care and Higher Case Cost in all Stages of CalWORKs Child Care

Parents have a right to receive CalWORKs child care as a supportive service while they participate in CalWORKs welfare-to-work activities and after they no longer receive CalWORKs cash aid, so long as they remain otherwise eligible for state child care programs. The Legislature determines CalWORKs child care slots and funding based on anticipated caseload. After several years of flat or declining numbers of children served in the CalWORKs child care programs, CalWORKs child care is projected to provide care for an additional 13,350 children over actual enrollment in 2017-18. 8

The Budget allocates an additional $111 million to pay for a combination of increased enrollment and increased cost per case in all three stages of CalWORKs child care. About $23 million of the increase is attributable to increased cost per case from implementing the final year of rate increases, and making the hold harmless provisions in the RMR permanent. The remaining funding is to pay for increased caseload, especially in Stage 2 and Stage 3 child care. Last year, California adopted 12 month continuous child care eligibility and increased its income eligibility limits. Since last July, families are no longer churning off Stages 2 and 3 child care, providing more stability for children and giving families the continuous care they need to thrive.

The Stage 3 caseload has already increased and both Stage 2 and 3 are projected to add an additional 13,051 children in this budget year. That brings the total number of children served through the three stages of the CalWORKs child care program to 141,837.

A breakdown of CalWORKs child care funding and enrollment follows.

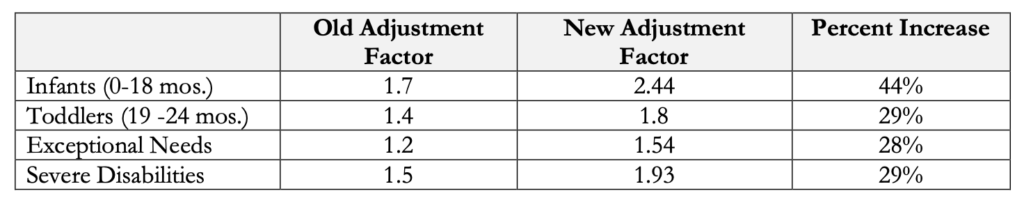

C. Increased Adjustment Factors for Infants/Toddlers and Children with Disabilities

The Budget increases the SRR adjustment factors for infants who are 0 to 18 months of age, and toddlers who are 18 to 36 months of age, and are served in a Title 5 child day care center or a Title 5 family child care home.13 It also increases the adjustment factors for all providers serving children with exceptional needs, and severely disabled children, both of whom are potentially eligible for care up to 21 years of age. As an example, the infant adjustment factor of 2.44 will increase the daily rate in a child care center for an infant to $117/day.14These increased adjustment factors will become effective January 1, 2019. The cost this year is $39.7 million, and ongoing costs will be $80 million.

These greatly increased rates for infants and toddlers should allow centers to open or expand their infant/toddler classrooms.

All seven categories of enhanced adjustment factors adopted by the Legislature are meant “to reflect the additional expense of serving children who meet any of the criteria outlined in paragraphs (1) to (7)…”15 For children with exceptional needs or severe disabilities, it “shall be used for special and appropriate services for each child for whom an adjustment factor is claimed.”16

The documentation requirements to qualify for reimbursement for the adjustment factors have not changed. CDE continues to require additional, burdensome verification for children with exceptional needs or children with severe disabilities. In order to claim the enhanced reimbursement, a provider must show not only that the child with exceptional needs has a current Individualized Education Plan or Individualized Family Support Plan, but also medical documentation and proof that the program has incurred additional ongoing service costs for that child.17 By contrast, all that is needed to qualify for the age-related adjustment factors is proof of the age of the child.

Not surprisingly, adjustment factors to serve children with disabilities are rarely granted. CDE reports that in 2016-17, only 3,214 children with exceptional needs were granted the adjustment factor statewide and 118 children with severe disabilities were granted the adjustment factor.18

D. Increase in Standard Reimbursement Rates and CSPP rates, with automatic COLA

This year saw the final year of SRR rate increases contained in the multi-year agreement, for a combined increase of 5.6% in the SRR. This is in addition to the increase in the adjustment factors, described above. The reimbursement rate for full-day center care increased from $11,360 to $11,995 and the reimbursement rate for full-day state preschool reimbursement rate increased from $11,432.50 to $12,070 effective July 1, 2018.

Further, beginning next fiscal year, these reimbursement rates are set to automatically receive a cost- of-living adjustment (COLA) that is pegged to that used by school districts.19 The combined cost for these increases in FY 2018-19 is $102 million.

E. Additional Full Day State Preschool Slots

The Budget fulfills the final year of the 2016-17 multi-year agreement by adding $8 million to fund 2,959 new full-day state preschool slots beginning April 1, 2018. This brings the total projected full-year enrollment to 168,478 part-day preschool spaces. In addition, the Budget funds full-day, full-year wrap-around care in both LEA-administered and general child care programs for 66,599 children. (All Proposition 98 except $176.4 million General Fund for the non-LEA wraparound).

F. One Time Funds for School District Early Education Expansion Grants

The Budget includes $167 million of Proposition 98 funds for one-time infrastructure grants to local educational agencies for the purpose of increasing access to inclusive early care and education programs. These grants are to encourage construction and improvements to facilities that serve all children; there is no requirement that a set percentage of children with special needs are to be served in that inclusive setting. The bill would require the department to award grants on a competitive basis, and would require the department’s Special Education Division and Early Education and Support Division to work collaboratively to administer the program. High-need school districts will be prioritized and 33% of the total award amount must be provided by local resources.20

G. Annual Inspections of all Licensed Child Care Providers

The Budget provides $26.4 Million of CCDBG Quality Improvement (QI) money to pay for annual inspections of licensed providers. The CCDBG Act of 2014 mandates that CCDF-funded licensed child care providers be inspected at least on an annual basis.21 Currently, the Community Care Licensing Division of CDSS inspects licensed child care providers a minimum of once every three years. The federal law also requires that a state conduct annual inspections of license exempt providers who are subject to Trustline, but funding for this was not included.

Early childhood advocates had unsuccessfully introduced legislation and funding proposals to assure annual inspections for all licensed child care providers for more than ten years.

H. Trailer Bill Language (TBL) Expands What LEA-Administered Preschool Classrooms will be exempt from CCLD Licensing

The Legislature once again waded into this contentious area, defining what LEA-administered classrooms would be exempt from licensing, and when LEA-administered commingled or blended preschool programs would be exempt from Title 22 licensing. The Legislature’s language demonstrates its intention to move forward with its proposal to allow school districts to be exempt from Title 22 licensing, with some minor protections added to Title 5 regulations. These mixed preschool and transitional kindergarten (T-K) classrooms could include children as young as 2.9 years of age along with 5 year olds.22

Commingled Programs: This year’s Budget agreement authorizes school districts or charter schools to commingle 4 year-old children enrolled in state preschool into a transitional kindergarten classroom. As of July 1, 2019, the commingled preschool and T-K program would be exempt from Title 22 licensing, so long as the classroom did not also include children enrolled in transitional kindergarten program for a 2nd year or kindergarteners.

Blended Programs – Many preschool programs blend or braid funding, such as CSPP and HeadStart funding, in the same classroom. The question arose during this year’s budget hearings and in the stakeholder process as to which licensing rules would apply to blended programs. TBL clarified that even $1 of CSPP funding would exempt that classroom from Title 22 licensing.

There is still considerable concern amongst legislators and child care stakeholders about the erosion of age and developmentally appropriate health and safety protections if the plan goes forward as of July 1, 2019. Parents will also lose the ability to see inspection reports and violations that have been issued against a particular preschool. CDE is now charged with promulgating regulations adopting the recommended health and safety protections identified by the LAO-run stakeholder group.

I. Child Care Quality Improvement Expenditure Plan

As a condition of receiving about $827 million this year in federal CCDF funding, California is required to spend a certain percentage of its federal and state matching funds on activities designed to improve the quality of child care services and increase parental options for, and access to, high quality care (Quality Improvement, or QI activities).23

California’s spending requirement is 11% for this fiscal year, and is set to increase to 12% by Federal Fiscal year (FFY) 2020. This includes 3% that must be spent on QI activities focused on infants and toddlers. California is required to spend a total of $91 million on QI in FFY 2019. This budget year, a total of $116.8 million is allocated for QI activities, including the $26.4 million for annual inspections (see “G,” above).

The Budget applies approximately $26 million of QI one-time carryover funds to a county pilot program to encourage inclusive child care ($10 million), an increase for the Child Care Initiative Program ($5 million), professional development ($5 million), and apparently for the consumer education database ($6 million).

The California Department of Education recently submitted its Quality Improvement Plan for 2019-21 to the federal Administration for Children and Families, detailing its plans for how it will spend this significant amount of money to improve quality in all sectors of CCDF-funded child care. A plan and expenditure strategy that works for all of California’s low-income children will: (1) steer away from the heavy tilt of expenditures at preschools and child care centers and instead focus additional resources and effort on the locations where infants and toddlers are more likely being cared for; (2) tie quality measures to workforce compensation in all child care settings; (3) incorporate only those evidence-based measures that are proven to have demonstrably positive impacts on child development; and (4) mitigate the effects of place-based and racial inequities, by adopting strategies that affirmatively embrace licensed and license-exempt family child care providers, particularly in immigrant and low-income communities. We will want to pay careful attention in the implementation of the CDE plan so that channeling quality dollars through QRIS does not magnify funding and quality disparities that disfavor low-income communities and the children served in those communities.

J. Administrative Changes

Alternative Payment Programs now have at least 12 months, and no more than 24 months, to expend the contract funds from that fiscal year.24

CDE is given $624,000 for the administration of the county pilot projects.

K. Related Budget Items Aimed at Improving the Lives of Children

Increase CalWORKs Grants by 10% – The Budget provides $90 million general funds to increase CalWORKs cash assistance grants by 10%, beginning April 1, 2019. The maximum CalWORKs grant will increase from $714 to $785 a month for a family of three, or rise from 40 percent to 44 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). The trailer bill also sets out a two-step process for raising the grants to at least 50% of FPL over the next two budgets pending appropriation of funds in those budgets. The projected cost is $280 million annually in future years.

The Budget also includes language that would adjust the CalWORKs grant based on annual changes to the cost of living, as measured by the California Necessities Index, beginning July 1, 2022. These adjustments are subject to appropriation in future budget acts.

This was a more modest timeline for grant increases than what is provided for in SB 982 (Mitchell), a bill that would increase the CalWORKs grant to prevent childhood deep poverty, defined as 50% of the Federal Poverty Level, and provide for automatic grant increases indexed to changes in the California Necessities Index.

Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) will receive an additional $10 million to provide meals for low-income children in proprietary child care centers.25

New Home Visiting Program – The Budget includes $27 million federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds to begin a new voluntary home visitation program within the CalWORKs program. It also sets aside an additional $131 million in TANF funding to support annual costs of the home visiting program in future years. Under the new program, CalWORKs families with a child under two years old will be eligible to receive regular visits from a nurse, parent educator, or early childhood specialist who works with the family to improve maternal health, parenting skills, and child cognitive development. Counties will prioritize limited home visiting funding to provide home visits for first-time parents under the age of 25.

Lead Testing and Remediation Program for Child Care Centers – The Budget provides $5 million for lead testing at licensed child care centers, and for remediation of lead in plumbing and drinking water fixtures. Priority is given to centers where at least 50% of children receive subsidized child care, and single facilities. In addition, the California Resource and Referral Network will provide technical assistance and outreach to family child care providers, but not remediation dollars.

III. Conclusion

The California Legislature has demonstrated its ongoing commitment to supporting families and children with bold new expenditures in child care and early education. Many legislators understand that supporting children from the beginning of their lives lays the foundation for a brighter future for everyone.

In addition to the state’s budget surplus of more than $8 billion,26 the state received an unexpected boost of $230 million more in federal CCDBG funds this year than in FFY 2017.27 California legislators wisely chose to target most of the new federal funds toward providing low- income children with the flexible and affordable child care parents need most. The state could have done even more if this significant new federal funding had been combined with a greater state fund contribution.

Now our state is well-positioned to build on this year’s successes and make significant increases in the availability of child care so that more California families can share our state’s prosperity.

Endnotes:

1 Budget Act of 2018, S.B. 840, 2017-18 Sess., Ch. 29 (Cal. 2018) (enacted); Education Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 1808, 2017-18 Sess., Ch. 32 (Cal. 2018) (enacted).

2 This total budget figure does not include $865 million for Transitional Kindergarten (T-K) programs which was historically part of the K-12 education budget, and whose allocation is based on the Local Control Funding Formula. Starting in 2017, the Legislative Analyst’s Office began including T-K in the preschool budget. CDE does not include T-K in its child care budget.

3 The Budget Act establishes total California early care and education program funding for 2018-19 at $4,621,543. Last year’s total enacted budget was $3,993,834. The increase from last year is $628 million, or 16%.

4 Kristin Schumacher, Child Care and Development Programs and the 2018-19 May Revision. Presentation at the California Child Development Administrators’ Conference, CALIFORNIA BUDGET & POLICY CENTER (May 2018).

https://calbudgetcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Kristin-Schumacher_California-Child-Development- Administrators-Association_05.18.2018.pdf

5 Budget Act of 2017, A.B. 97, 2017-18 Sess., § 2.00, Item 6100-194-0001 (Cal. 2017) (enacted).

6 Budget Act of 2018, supra items 5180-101-0001, 5180-153-0001 and 5180-151-0001 (Cal. 2018) (enacted), re-appropriating unspent funds allocated in the 2017-18 budget year.

7 Dept. of Finance: California Child Care Programs. Local Assistance-All Funds. 2018-19 Budget Act.

8 The total increase in the CDE budget for CalWORKs Stages 2 and 3 is $104 million, with an additional $11 million in the CDSS budget for Stage 1 child care.

9 Dept. of Finance: California Child Care Programs. Local Assistance-All Funds. 2018-19 Budget Act. https://cappa.memberclicks.net/assets/StateBudget/2018-19/DOF%20DMC%202018-19%20BA.pdf.

10 The number of children reflects the total number of children that can be served for a full year, based on the program’s appropriation. These estimates are based on average cost of care per full year per case, and do not reflect the actual number of children served in each CalWORKs child care program.

11 For Stage 2 and 3 enrollment data, see Department of Finance: California Child Care Programs, Local Assistance-All Funds: 2018-2019 Budget Act. For Stage 1 enrollment data, see Cal. Dep’t. of Soc. Servs. Child Care Monthly Report CalWORKs Families (CW 115) FY 2017-18, http://www.cdss.ca.gov/Portals/9/DSSDB/DataTables/CW115FY17-18.xlsx; see also Child Care Monthly Report CalWORKs Families (CW 115A) FY 2017-18, http://www.cdss.ca.gov/Portals/9/DSSDB/DataTables/CW115AFY17-18.xlsx.

12 This year’s Stage 2 CalWORKs child care budget reduces the TANF funding from $130 million to $80.6 million and increases the general funding from $389 million to $479.3 million. Source: Department of Finance: California Child Care Programs. Local Assistance-All Funds. 2017-18 Budget Act.

13 Cal. Educ. Code § 8265.5 (West 2016).

14Budget Act of 2018, supra item 6100-194-0001, Provision 5. 15 Cal. Educ. Code § 8265.5.

16 Education Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 1808, 2017-18 Sess., Ch. 32, § 11 (Cal. 2018) (enacted) (amending Cal. Educ. Code § 8265.5). Children are considered to have “exceptional needs” if they are either an infant or toddler with a developmental delay or established risk condition, or are at high risk of having a substantial developmental disability — or a child age 3-21 who has been determined to be eligible for special education and related services by an individualized education program team. This includes “severely disabled children.” Cal. Educ. Code § 8208(l) and (x)).

17 Cal. Code Regs., tit. 5, § 18075.2. But see, Cal. Code Regs., tit. 5, § 18089 (2018).

18 Cal. Dept. of Education, Early Education and Support Division (EESD), “Exceptional Needs Average

Child Count Fiscal Year 2016-17”; “Severely Disabled Average Child Count Fiscal Year 2016-17.”

19 School Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, S.B. 842, 2017-18 Reg. Sess., § 10, (adopting the cost-of living adjustment found in Cal. Educ. Code § 42238.15).

20 Education Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, supra § 12 (Cal. 2018) (enacted).

21 Consolidated Appropriations Act, H.R. 1625, 115th Cong. (2018); Health and Safety Requirements, 45

C.F.R. § 98.41 (2016).

22 Budget Act of 2018, supra, § 9 (Cal. 2018) (enacted).

23 Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) Act of 2014 § 6, 42 U.S.C. § 9858e (West 2017) (Quality Spending Requirement); 45 C.F.R. § 98.50(b) (West 2017). See FY 2018 CCDF Allocations: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/fy-2018-ccdf-allocations-based-on-appropriations.

24 Education Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, supra, § 7 (Cal. 2018) (enacted) (amending Educ. § 8220.1(d)(1)). “ . . . [A]lternative payment programs shall have no less than 12 months, and no more than 24 months, to expend funds allocated to that program in any fiscal year.” Id.

25 Budget Act of 2018, supra item 5180-101-0890 (Cal. 2018) (enacted).

26 California Budget & Policy Center Report, 2018-19 State Budget Invests in Reserves and an Array of Vital Services, Sets Course for Future Advances (June 2018). The California Budget and Policy Center reports that the final budget set aside $3.5 billion, with half going to the state’s rainy day fund and half to pay down debts. An additional $2.6 billion is deposited into a new, temporary reserve; $2 billion is placed in a discretionary reserve; and a new $200 million “safety net reserve” is created to help support CalWORKs and Medi-Cal services in an economic downturn. State reserves are expected to total almost $16 billion by the end of 2018-19.

27 Total FY 2017 CCDF allocation for California was $601,559,726; total FY 2018 CCDF allocation for California is $827,230,552. Compare, FFY 2017 and 2018 CCDF Allocations: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/fy-2018-ccdf-allocations-based-on-appropriations, with https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/fy-2017-ccdf-allocations-including-redistributed-funds.