The California Legislature passed the Budget Act of 2017, Assembly Bill 97 (AB 97), and related statutory changes (AB 99 and SB 89) necessary to enact the Budget Act on June 15, 2017.1 The Governor signed these budget bills for the 2017-18 fiscal year (the “Budget”) on June 27, 2017. The following analysis addresses key child care and early education items in the Budget in light of recent funding history and alternative proposals that were considered during this year’s budget process. Total funding for all child care and development programs, including State Preschool and afterschool programs, increased by more than $320 million.

The budget process began with a great deal of fiscal uncertainty, primarily stemming from dire predictions regarding impending cuts to federal funding and reimbursement in a range of programs, particularly the federal Medicaid program and the Affordable Care Act. The 2016- 17 budget agreement included a plan to increase child care and preschool funding by about $500 million over four years. In January, the Governor proposed delaying implementing the second year of provider rate increases and additional full-day preschool slots for one year. By the time of the May Revise, the Governor proposed restoring the scheduled second year of provider rate increases and additional 2,959 preschool slots, and these items are contained in the final Budget.

The Legislature demonstrated its ongoing commitment to building strong child care and development programs. This year, legislators focused on updating and improving family eligibility policies and fulfilling the second year of the multi-year budget agreement with its across-the-board provider rate increases and preschool expansion.

We have made key improvements over the last three years that will positively impact child care providers and families, creating a more sustainable and stable child care program. We can now turn our attention to the dire shortage of available, affordable child care, particularly for infants and toddlers. Too many children in California still do not have access to affordable, high- quality early childhood care and education during their first five years of life. Currently, only one in seven eligible children ages 0-12 have access to full-day, year-round care in our subsidized child care and development programs.2 Child Care Law Center joins the Legislative Women’s Caucus and many others in strongly recommending that California prioritize new funding to increase the number of families who benefit from good, stable and affordable child care.

I. Overview of Child Care and Early Education Funding in FY 2017-2018

Total funding for child care and development programs increased $320 million over the budget for the prior fiscal year, bringing the total to $3.9 billion. The Budget continues implementation of the multi-year investment in California’s subsidized child care and development programs that was part of the 2016-17 budget agreement. It also makes substantial progress in raising family income eligibility guidelines for subsidized programs, which had not

been updated in a decade, and improving family stability by adopting 12 months of continuous eligibility (“12-month eligibility”). Both the increases in provider reimbursement rates and family eligibility reforms help fulfill the promise of greater economic security that California made when it adopted incremental increases to the state minimum wage.

The highlights of specific increases contained in this year’s budget package are:

- $25 million to update income eligibility limits and adopt 12-month eligibility periods. The new family eligibility guidelines are set at 70% of the most current State Median Income (SMI) to initially qualify for subsidized child care.3 Once eligible, families can keep their affordable child care until their income reaches 85% of current SMI. The budget also adopts a true 12-month eligibility period, where families remain eligible regardless of changes in income or need, as long as family income does not exceed 85% of state median income.4 These changes took effect July 1, 2017.5

- $92.7 million to increase the Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR) for State Preschool and other child care providers that contract directly with the state. The budget annualizes last year’s SRR increases and restores the promised 5%increase in SRR that had been temporarily “paused” in the Governor’s initial budget proposal. In addition, the 2017-18 budget increases the SRR by an additional 6.16%. Both increases are effective July 1, 2017 ($60.7 million Prop. 98; $32 million non-Prop. 98 General Fund).6

- $40.6 million to update the Regional Market Rate (RMR) to 75th percentile of the 2016 RMR Survey. The budget package increases the value of vouchers by updating rates to the 75th percentile of the 2016 Regional Market Rate Survey, effective January 1, 2018.7 There is also a one year hold harmless provision.8

- $19 million for emergency child care vouchers for children in out-of-home placements, with a commitment for $31 million in ongoing annual funding in subsequent years. The Emergency Child Care Bridge Program for Foster Children will pay for short-term child care services in participating counties, and for navigators based in the local resource and referral agencies to help fostering families find child care, and to provide training in trauma-informed care for providers. Effective January 1, 2018. ($15 million General Funds; $4 million Title IVE).9

- $7.9 million to add 2,959 full-day slots in the State Preschool program. The budget package adds 2,959 full-day state preschool slots administered by Local Education Agencies (LEAs), beginning March 1, 2018. These slots and timeline were part of the multi-year plan in the 2016-17 budget agreement. (Proposition 98 funded).

- $50 million to increase provider reimbursement rates for the After School and Education Safety Program (ACES). (Proposition 98 funded).

- $1.8 million to the San Gabriel YMCA to build a child care facility for underprivileged and homeless youth.

- Annualizing the mid-year rate increases from the prior year’s budget, with their time-limited hold harmless provisions.

II. Analysis of the Enacted Budget

The Budget will allow child care provider rate increases to keep on track with the multi- year agreement meant to reflect incremental increases in the state minimum wage, and other market forces. The increase in reimbursement rates will offer some relief to child care providers, who struggle to meet increased operating costs. It will also expand parents’ child care options because more child care providers will be willing to accept the higher subsidies, the options for quality care will expand, and parent co-payments will go down. Below is an analysis of Budget highlights:

A. Long-Awaited Improvements in Family Eligibility: Income Guidelines Increased to 70% of most recent SMI with a Graduated Phase-out; 12 Month Eligibility

Finally, after a decade of families losing affordable child care due to a frozen eligibility ceiling, the Budget updates the State Median Income (SMI) guidelines for all subsidized child care programs. The recently published income eligibility ceiling is based on the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau, using SMI data from 2015. This will allow parents who receive small financial benefits from the increasing minimum wage to be able to keep their affordable child care. Further, this eligibility ceiling will be updated annually, based upon the most current SMI annual survey available. Once found eligible, families will remain eligible for 12 months; they will not be required to report income changes, or be discontinued from affordable child care, until their income reaches 85% of the most recent SMI.

These budget changes fund and enact all the provisions of A.B. 60, “The Child Care Protections for Working Parents” bill (Santiago, Gonzalez Fletcher) which was sponsored by Child Care Law Center, Parent Voices and First 5 California.10

The California Department of Education (CDE) has worked with the Department of Finance to promptly issue three Management Bulletins (MB’s) to implement the updated entry and exit income ceilings: MB 17-08, State Median Income (Initial Certification), MB 17-09, Graduated Phase-out (Recertification), and MB 17-10, Updated Income Rankings. Additional Management Bulletins governing the revised Family Fee Schedule, 12 month eligibility and other changes described in this memorandum are expected to be issued shortly.

The Child Development Block Grant (CCDBG) Act of 2014 requires states to implement a number of policies to further the program’s dual purpose of “promoting children’s healthy development and school success and … support[ing] parents who are working or in training or education.”11 Improving the stability of child care assistance is a key component of the CCDBG Act of 2014, and California is now complying with the Act’s requirement that states implement a number of policies to promote stable child care assistance. These include that every child in Child Care and Development-funded (CCDF) programs is considered to meet all eligibility requirements and receives program assistance for not less than 12 months before the state redetermines eligibility, regardless of a temporary change in parental employment, job training or educational program activity, or a change in family income, so long as that income does not exceed 85% of the current state median income. 42 U.S.C. §9858c(N)(i)(I).

These changes are not only legally mandated – they are good policy. With implementation of these changes, California is a national trailblazer on its implementation of family eligibility policies that will make a significant positive impact on the lives of children and families.

B. The Budget Expands Preschool Availability and Focuses on Enrollment

The only funding in this year’s budget aimed at increasing the number of children served in early care and learning settings was in the California State Preschool Program (CSPP). The final budget included an additional $7.9 million to fund 2,959 new full-day CSPP openings.12 This brings the total funding for CSPP to approximately $1.2 billion, all funded through Proposition 98.

Over the past three years, the Legislature has created almost 13,000 new full-day State Preschool slots, with almost all to be administered by Local Education Agencies (LEAs). The rate at which LEAs have contracted for these slots has been disappointingly low, and the Legislature has expressed interest in determining the reasons for this low uptake. In 2014-15, $101 million, or 12% of all preschool dollars, was returned to the state because the allocations were not contracted or earned by providers.

Policy changes contained in the budget were aimed at increasing enrollment of 3- and 4- year-old children in part-day and full-day preschool programs, and addressing some of the reasons why a large percentage of preschool slots are currently not being contracted or used.

One of these policy changes contained in Trailer Bill Language accompanying the budget allows part-day California State Preschools, after all income-eligible children are enrolled, to provide services to 3- and 4-year-old children in families whose income is above the income eligibility threshold if those children have been identified as “children with exceptional needs,” as defined.13 These children will not count against the 10% limit on children from families above the income eligibility threshold.

C. Proposed Exemption of LEA-administered Preschools from CCLD Licensing and convening of a Title 22 Regulatory Stakeholder Workgroup

The Budget also includes a plan that by July 1, 2019, LEA-administered California State Preschool Programs that meet certain requirements will become exempt from the California Code of Regulations, Title 22 licensing and safety and health provisions.14 Currently these standards apply to all programs serving 3- and 4-year-olds, regardless of whether they are administered by a school district or a Title 5 center, or where they are physically located. LEAs have argued that preschools operating on school grounds and administered by LEAs already comply with Title 5 regulations and other legal requirements imposed on school facilities, and exempting LEA-administered preschools from Title 22 regulations would streamline the approval process, eliminate duplicative regulations and create more efficiencies.

Title 22 standards provide a foundation of health and safety protections specific to the needs of children under age five. Additionally, Title 22 regulations contain important inspection and oversight components to protect the health and safety of our youngest learners. Title 22 regulations contain, for example, the following requirements not found in Title 5:

- Initial licensing and inspection of the safety of physical surroundings, with an emphasis on hazards to very young children;

- Regular, unannounced health and safety inspections;

- Parent (consumer) access to a transparency website where individual facility

inspection reports, licensing status, complaints and their resolution are posted and may be reviewed;

- Confidential, on-line complaint process which triggers an inspection within 10 days;

- Sanitary and adequate toilet facilities.

Toward the end of the budget process, there was an abbreviated discussion of this proposal in legislative budget hearings. Recognizing the need for further discussion of the policy ramifications, the Budget adopted a more thoughtful process for determining what regulations were truly duplicative, and which were still needed.

The Legislative Analyst Office must convene a stakeholder group by October 1, 2017, for the purpose of identifying where there are redundancies in licensing or health and safety protections, while ensuring that state preschools operated by LEAs maintain all existing necessary health and safety requirements. The stakeholder group report and recommendations will be submitted to the appropriate fiscal and policy committees of the Legislature, CDE and the Department of Finance, no later than March 15, 2018. The process anticipates that, no later than July 1, 2019, LEA- administered preschools that meet these yet-to-be identified necessary health and safety requirements and operate in school buildings, as defined by the law, would become exempt from the provisions of the Day Care Facilities Act, including licensing provisions.

D. CalWORKs Child Care Programs

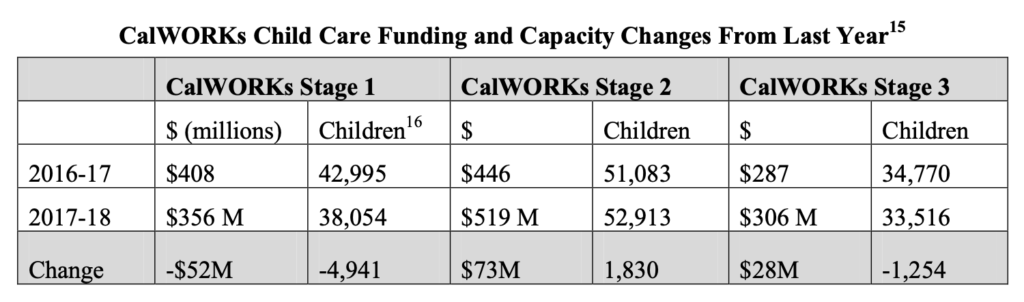

Parents have a right to receive CalWORKs child care as a supportive service while they participate in CalWORKs welfare-to-work activities and after they no longer receive CalWORKs cash aid, so long as they remain otherwise eligible for state child care programs. The Legislature determines CalWORKs child care slots and funding based on anticipated caseload. The three stages of CalWORKs child care received an increase of $199 million in FY 2015-2016 to pay for an additional 5,600 child care slots and increased rates to child care providers. This year’s CalWORKs child care funding reflects the combined effect of increased provider reimbursement rates, a lower than expected caseload in FY 2015-16, and a further anticipated reduction in CalWORKs child care caseloads.

This year’s CalWORKs child care budget continues the trend of offsetting state funds with available federal funds. In this budget, Stage 2 child care costs are paid for using an additional $120 million in federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant funds, offset by $27 million less in available federal CCDF funding. These TANF funds are mostly available due to a reduction in the CalWORKs caseload, and attendant cost savings.

Reduced Stage 1 caseload could be attributable to the ongoing reductions in the numbers of families who are receiving CalWORKs cash aid. However, given the increased rate of participation in welfare-to-work activities, it may also be a reflection of low rates of Stage 1 utilization by families currently engaged in welfare-to-work activities.17 Stages 2 and 3, which serve former participants in the CalWORKs program, have also seen fewer children served.

The increases in Stages 2 and 3 funding are based on a combination of increased Regional Market Rate (RMR) reimbursement ceilings and the estimated $25 million cost of raising the family eligibility guidelines and adopting 12 month eligibility. Despite the increased funding for these two programs, this will not allow for any significant increase in overall Stage 2 and 3 caseloads.

E. No Increase in Alternative Payment Program Vouchers; the Need to Expand Programs for Infants and Toddlers is Greater than Ever

This year’s budget demonstrates the Legislature’s steady commitment to child care and early education, and lays a foundation for serving more eligible children and improving family stability without impoverishing child care providers. At the same time, California has restored less than one third of the 110,000 spaces in state subsidized child care programs lost during the Great Recession. Child care investments over the last four years have tilted heavily toward pre- school children (ages 3-5), much of that paid for with Proposition 98 dollars. However, the need for infant and toddler (ages 0-3) child care remains particularly acute.

Now that we have fortified the foundation of our child care “house,” through increases in provider rates and family eligibility guidelines, we are ready to build our needed expansion. We fully endorse the Legislative Women’s Caucus’ call for $500 million in funding to be applied to general child care and Alternative Payment (AP) slots.

F. Child Care Quality Improvement Expenditure Plan

As a condition of receiving about $640 million annually in federal CCDF funding, California is required to spend a certain percentage of its federal and state matching funds on activities designed to improve the quality of child care services and increase parental options for, and access to, high quality care (Quality Improvement, or QI activities). California’s spending requirement is 7% for this fiscal year, and is set to increase to 9% by 2020-2021. An additional 3% of overall spending must be spent on QI activities focused on infants and toddlers.18

California was required to spend a total of $78 million on QI in the last budget year and again in the current year. This budget year, a total of $82.4 million is directed at QI activities, slightly less than last year. The Legislature once again directed that, to the greatest extent possible, CCDBG quality dollars should support the Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS), although it also asserts that the state should maintain funding for resource and referral agencies, local planning councils and licensing enforcement, all of which compete with QRIS for quality dollars to implement specific quality improvement initiatives.

Additionally, research to date indicates a weak link between QRIS measures and improvements in child development outcomes.19 Before we invest more funds in QRIS initiatives, we should develop, test and incorporate measures that are shown to produce positive outcomes. The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) estimates that California will need to spend a total of $95 million on QI by 2020, so it is worthwhile now to re-formulate a comprehensive plan and expenditure strategy that: (1) steers away from the almost exclusive expenditures at preschools and child care centers and instead focuses additional resources and effort on the locations where infants and toddlers are more likely being cared for; (2) incorporates only those evidence-based measures that are proven to have demonstrably positive impacts on child development; and (3) does not exacerbate potential place-based and racial inequities. We will want to pay careful attention in the implementation of the CDE plan that channeling quality dollars through QRIS does not magnify funding and quality disparities that disfavor low-income communities.

G. Miscellaneous Budget Items Will Ease Administrative Burdens and Align Child Care Definitions with Other Programs Serving Children.

1. Expands the definition of homeless child or youth to match the McKinney-Vento Homeless Act

This clarification will incorporate the broader definition of the term “homeless children and youths” found in the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (“McKinney-Vento”). Most federal and state programs, including HeadStart and the Department of Education, determine whether a child and her family are homeless using this definition.20 The definition of “homeless” currently in Title 5, § 18078 (h) and used in our state subsidized child care programs will need to be amended. CDE plans to issue a Management Bulletin in the interim to advise the field of this more detailed and inclusive definition. This change is significant because a homeless child is eligible for child care services, automatically meeting both categorical and service need requirements.21

The alignment of the definition with federal law will bring consistency to the treatment of homeless children and youth as they pass from the early child care to the K-12 educational system.

2. Authorizes Alternative Payment Programs and contractors to use digital application forms

Alternative Payment Programs (APP’s) and contractors were previously authorized under state law to maintain records electronically, including attendance records, and to use digital signatures.22 This new provision permits, but does not require, the additional use of electronic application forms, which has the potential to make the application process easier, particularly for working parents.

III . Conclusion

The reinvestment in all child care and early education programs of an additional $320 million will help working parents obtain and keep safe, quality child care while offering much needed increases in payment rates for child care providers. The budget allocation in child care and early education, while significant, did not substantially reduce the number of eligible children languishing on waiting lists. However, the dedication of policymakers to a multi-year commitment to early education and child care and the continued reinvestment holds out hope for further progress. The Child Care Law Center strongly urges further financial support for child care and early education to increase the availability of child care so that more California families can join in the promise of increased opportunities and a shared prosperity.

Endnotes:

1 Budget Act of 2017, A.B. 97, 2017-18 Sess. (Cal. 2017) (enacted); School Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 99 Sess. (Cal. 2017) (enacted) (provides for statutory changes necessary to enact the K- 12 statutory provisions of the Budget Act of 2017); Human Services, S.B. 89, 2017-18 Sess. (Cal. 2017) (enacted) (provides for statutory changes necessary to enact human services-related provisions of the Budget Act of 2017).

2 Kristin Schumacher, Over 1.2 Million California Children Eligible for Subsidized Child Care Did Not Receive Services From State Programs in 2015, CALIFORNIA BUDGET & POLICY CENTER (Dec. 2015), http://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/1-2-million-california-children-eligible-subsidized-child-care-not- receive-services-state-programs-2015/. An estimated 1.5 million children from birth through age 12 were eligible for care, according to the Budget Center analysis of federal survey data. However, only 218,000 children were enrolled in programs that could accommodate children for more than a couple of hours per day and throughout the entire year.

2 School Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 99, 2017-18 Sess., § 10 (Cal. 2017) (enacted) (amending Cal. Educ. Code § 8263.1). The most recently issued U.S. Census data on state median income will be used to determine family eligibility guidelines, to be updated annually. In issuing new family eligibility guidelines in July 2017, CDE appropriately used the 2015 SMI data published in October 2016. The 2016 SMI data will be published in October 2017, and will result in an update to the SMI guidelines no later than May 1, 2018.

4 Id.

5 The California Dept. of Education has already issued three Management Bulletins to implement these changes, with more to follow: Cal. Dep’t of Educ., Management Bulletin (MB) 17-08, State Median Income (Initial Certification) (2017); Cal. Dep’t of Educ., MB 17-09, Graduated Phase-out (Recertification) (2017); and Cal. Dep’t of Educ., MB 17-10, Updated Income Rankings (2017).

6 Beginning in January 1, 2017, the standard reimbursement rate (SRR) for a 250-day year at a center increased to $10, 529.75 per unit of average daily enrollment, and the full-day state preschool reimbursement rate rose to $10,595.75. As of July 1, 2017, the SRR is increased to $11,360.00 and the full-day state preschool reimbursement rate will be $11,432.50. The SRR rate can be further adjusted upwards based on factors such as age, exceptional needs, and no or limited English speaking.

7 Budget Act of 2017, A.B. 97, 2017-18 Sess., § 2.00, Item 6100-194-0001 (Cal. 2017) (enacted).

8 School Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 99, 2017-18 Sess., § 13 (Cal. 2017), amending Cal. Educ. Code § 8357(a)-(c). Last year’s budget had raised the RMR to the 75th percentile of the 2014 RMR survey, and also contained a time-limited hold harmless provision preventing providers from receiving less than they would have due to the updating of the RMR. This year’s budget revised the end date of the current time-limited hold harmless provision so that it expires on December 31, 2017 (not June 30, 2018), It also added a new hold harmless provision, in effect from January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2018, ensuring a provider will receive the greater of the reimbursement rate under the 2016 RMR survey or the RMR ceiling that existed in that region on December 31, 2017.

8 CCDBG Act of 2014 § 6, 42 U.S.C. § 9858e (West 2017) (Quality Spending Requirement); 45 C.F.R. § 98.50(b) (West 2017).

9 Human Services, S.B. 89, 2017-18 Sess., § 35 (Cal. 2017) (enacted) (amending CAL. WELF. & INST. CODE § 11461.6).

10 Subsidized Child Care & Development Services: Eligibility Periods, A.B. 60, 2017-18 Sess. (Cal. 2016).

11 U.S. Office of the Administration for Children & Families; Office of Child Care, “CCDF Reauthorization Frequently Asked Questions,” at https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/ccdf- reauthorization-faq-archived.

12 School Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 99, 2017-18 Sess., § 13 (Cal. 2017) (enacted) (amending Cal. Educ. Code § 8357(a)-(c)).

13 School Finance: Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, A.B. 99, 2017-18 Sess., § 7 (Cal. 2017) (enacted) (amending Cal. Educ. Code § 8235(d)). Children are considered to have “exceptional needs” if they are either an infant or toddler with a developmental delay or established risk condition, or are at high risk of having a substantial developmental disability — or a child age 3-21 who has been determined to be eligible for special education and related services by an individualized education program team. This includes severely disabled children. Id. at § 5 (amending Cal. Educ. Code § 8208(l)).

14 AB 99, Ch. 15, Sec. 69, amending Cal. Health & Safety Code § 1596.792 to add a new exemption from CCLD licensing. This exemption will take effect via emergency regulations, or no later than July 1, 2019.

15 Source: Department of Finance: California Child Care Programs. Local Assistance-All Funds. 2017- 18 Budget Act.

16 The number of children reflects the total number of children that can be served for a full year, based on the program’s appropriation. These estimates are based on average cost of care per full year per case, and do not reflect the actual number of children served in each CalWORKs child care program.

17 CalWORKs Annual Report, 2017 at http://www.cdss.ca.gov/calworks/res/pdf/CW_AnnualSummary2017.pdf.

18 CCDBG Act of 2014 § 6, 42 U.S.C. § 9858e (West 2017) (Quality Spending Requirement); 45 C.F.R. § 98.50(b) (West 2017).

19 Chaudry, A.J., et al., “Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality,” p. 60. Russell Sage Publications (2017)

20 McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, 42 U.S. Code § 11434a(2). The term “homeless children and youths”

(A) means individuals who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence…; and [are]

- (i) …sharing the housing of other persons due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or a similar reason; are living in motels, hotels, trailer parks, or camping grounds due to the lack of alternative adequate accommodations; are living in emergency or transitional shelters; or are abandoned in hospitals;

- (ii) …have a primary nighttime residence that is a public or private place not designed for or ordinarily used as a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings;

- (iii) …living in cars, parks, public spaces, abandoned buildings, substandard housing, bus or train stations, or similar settings; or

- (iv) …migratory children living in any of the above settings.

21 Cal. Educ. Code § 8263(a)(1)(A)(iii), 8263(b)(i)(III); 5 Cal. Code Regs. §§ 18085.5, 18090, 18091 (documentation of homelessness and of seeking housing).

22 Cal. Ed. Code §8221.5(c) (monthly attendance records may be kept in electronic format); id. at § 8227.3 (APP’s and providers may maintain records electronically); id. at § 8227.5 (use of digital signature).